Blurry Vision: Ruling Sheds Doubt on Defenses to Discrimination Claims

In previous posts (here and here), we discussed a federal case in Texas (Braidwood Management v. EEOC) that addressed several legal defenses and exceptions for religious employers accused of violating sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) laws. The Braidwood decisions discussed in the linked posts held that faith-based employers might have multiple constitutional and statutory defenses from liability for SOGI discrimination so they could select employees who were aligned with their organization’s religious beliefs.

However, a recent decision from a federal court in Washington State goes the other way, interpreting religious exemptions to SOGI discrimination laws quite narrowly. This post discusses this recent decision and its implications for religious employers.

Background

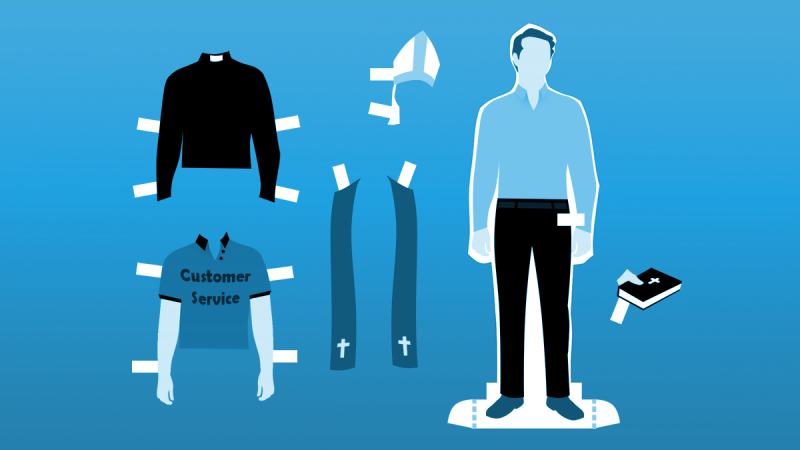

World Vision, a Christian humanitarian organization, offered Aubry McMahon a position as a customer service representative. However, after learning that McMahon was in a same-sex marriage, World Vision rescinded the job offer based on its statement of faith “that marriage is a Biblical covenant between a man and a woman.” McMahon sued World Vision under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act and a similar Washington statute, for discrimination on the basis of sex, sexual orientation, and marital status.

World Vision filed a motion for summary judgment asserting several statutory and constitutional defenses against McMahon’s discrimination claims. The federal district court rejected all of World Vision’s arguments and refused to dismiss McMahon’s claims.

World Vision’s Statutory Arguments

World Vision made two arguments based on the provisions of Title VII itself. First, it asserted that the “religious corporation exception” under Title VII barred McMahon’s discrimination claims. This exception provides that Title VII does not apply “to a religious corporation, association, educational institution, or society with respect to the employment of individuals of a particular religion to perform work connected with the carrying on by such corporation, association, educational institution, or society of its activities.”1

World Vision argued that this exception applied because its decision to rescind McMahon’s employment offer was based on the fact that her beliefs and conduct were inconsistent with the organization’s statement of faith. However, the court rejected this argument, ruling that this defense only immunized religious organizations against claims for discrimination based on religion, not discrimination based on sexual orientation.

World Vision also argued that affirming its statement of faith with respect to marriage and sexuality was a “bona fide occupational qualification” (BFOQ) under Title VII. The relevant provision of Title VII permits an employer to discriminate on the basis of “religion . . . in those certain instances where religion . . . is a bona fide occupational qualification reasonably necessary to the normal operation of that particular business or enterprise.”2

World Vision believed that being a Christian in conformity with its statement of faith was a necessary qualification of being a customer service representative for the organization. The court, however, rejected this argument, finding that there was nothing to indicate “that being in a same-sex marriage affects one’s ability to place and field donor calls, converse with donors, pray with donors, update donor information, upsell World Vision programs, or participate in devotions and chapel.”

World Vision’s First Amendment Arguments

World Vision asserted several First Amendment arguments in its attempt to get McMahon’s claims dismissed. First, it argued that the claims were barred by the ministerial exception. As we have previously discussed, the ministerial exception is a First Amendment doctrine stating that religious organizations have the right to select their “ministers” without government intervention. Unlike the Title VII religious exception, the ministerial exception applies to bar all discrimination claims, not just those for religious discrimination. The application of this doctrine, however, comes down to whether the employee in question is a “minister,” and depends on whether an employee performs important religious functions.

World Vision argued that the customer service position McMahon had applied for was that of a minister and the ministerial exception therefore applied. The court rejected this argument for several reasons. First, it found that the position title “customer service representative” was secular in nature. Second, it found that the position “did not require any kind of formal religious education or training.” Finally, although World Vision expected that a customer service representative would likely lead devotions and worship and pray with donors, the court found that these activities were not strictly required for the position.

World Vision also argued that the application of SOGI anti-discrimination laws to its selection of representatives violated its rights under both the Free Exercise Clause and the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment. But the Court also rejected these arguments. Its ruling on Free Speech is in most direct tension with the Braidwood decision. In Braidwood, the trial court ruled that a religious employer’s right to “expressive association” under the Free Speech Clause was a defense to SOGI discrimination claims. Indeed, World Vision cited the Braidwood ruling in its motion, but the court rejected the Braidwood decision as “unpersuasive.”

Seeing Clearly: Implications for Religious Employers

This decision is one of a handful in recent years that address these same arguments in this same religious employer context. While there is no clear consensus among the federal courts on these issues (and someday the Supreme Court will probably resolve the issue), religious employers should take steps to strengthen their defenses.

First, religious employers should have clear and detailed job descriptions. For positions that an employer treats as ministerial in nature, the descriptions should clearly state that religious functions are required in the role and employees should agree to this in writing. For all positions, any religious requirements should be spelled out. This will be critical in establishing ministerial exception and BFOQ defenses.

Second, religious employers should have clear organizational statements of faith that express the organization’s religious tenets on issues of marriage and sexuality so that employment decisions can be made on the basis of religious belief, without being facially discriminatory on the basis of SOGI.

Third, religious employers should word carefully any employment decision based on the organization’s religious beliefs, keeping in mind that the employee may argue that the decision was made on the basis of SOGI or other protected classes.

Most importantly, religious employers should consult with experienced legal counsel who are knowledgeable about these areas of employment liability for religious organizations.

_________________________________________

1 42 U.S.C. § 2000e–1(a).

2 42 U.S.C. § 2000e–2(e)(1).

Featured Image by Rebecca Sidebotham.

Because of the generality of the information on this site, it may not apply to a given place, time, or set of facts. It is not intended to be legal advice, and should not be acted upon without specific legal advice based on particular situations